- Blog

-

THESIS

- MISSION: Learning science by doing science.

- ARGUMENTATION: The missing piece to inquiry.

- IMPLEMENTATION: Teaching students to think like scientists

- FINDINGS: Student growth and response to argumentation frameworks

- REFLECTION: Co-generative thoughts for future practice

- ARTIFACTS: Data from the field and the study

- Portfolio

- About

|

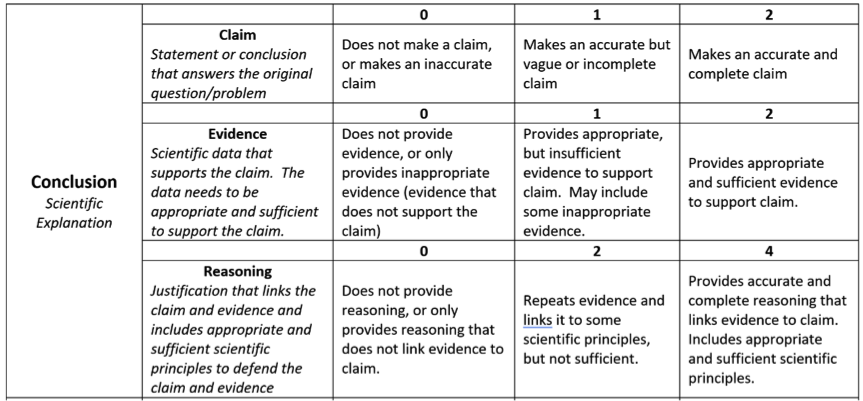

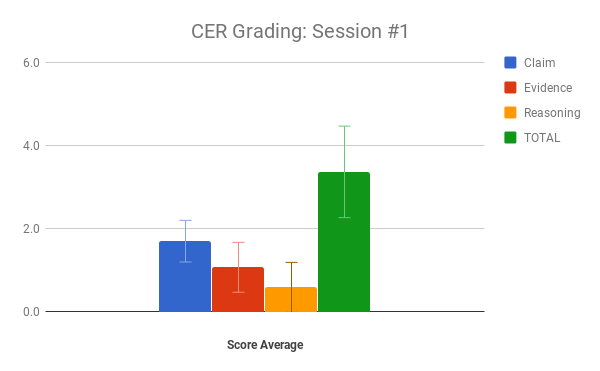

What happens when I teach science students how to form arguments? In my previous post, I outlined a lesson where I introduced CER frameworks to my students. The goal here was to offer scaffolds to build stronger scientific explanations. Ideally, by learning how to make their thinking visible, students would then develop their skills in explaining and solving scientific problems. So, how’d it turn out? In general, students had trouble adjusting to this new method of learning and assessment. Most said they were not used to writing at length in a science class. For them, this was more akin to the work of an English or a History class. And they're right: I never did work like this in high school either! But, so much more than memorizing textbooks and bubbling in exams, this mirrors the practices that scientists follow everyday. And if our goal is to learn science by doing science, then developing explanations and arguments is one of the best ways to go. It's a departure from traditional methods, but more and more teachers are beginning to shift focus towards these skills. Nonetheless, this was a new experience for students. So we used a rubric to break down each component of argumentation into a concrete framework. Throughout my thesis investigations, I'll be tracking student progress according to this rubric. First results below! Here’s how we scored. Claim: 1.7 ± 0.5 Evidence: 1.1 ± 0.6 Reasoning: 0.6 ± 0.6 TOTAL: 3.4 ± 1.1 (n = 48) Claims were simple and easy. Students varied in the quality of their responses, but typically were strong at coming up with claims. This makes sense; it was a yes/no question. However, some students still provided unstructured or incorrect claims. It will be important to strengthen this skill quickly, because future prompts will be made much more complex. Evidence was more difficult. While many students did a fine job researching and gathering supporting ideas, they were not always relevant. Often, they presented flawed or unrelated evidence. Other times, they simply rehashed scientific ideas to spin them as evidence. Not good enough. Future lessons will need to emphasize that evidence most often comes in the form of data. Reasoning was most difficult. Students received the lowest scores here. (The lower end of the error bar here even went all the way to zero!) Sometimes, similar to above, students would give scientific evidence but offer nothing else. And often they failed entirely to elaborate on why their arguments make sense. As predicted, this is one of the hardest skills for students to develop. How to build on this? Throughout the next several lessons, I want to implement more opportunities for students to practice argumentation. They don't necessarily have to look like the one above; they can range from written passages to verbal explanations, visual modeling, and class-wide discussions. I'll be working each of these in and gathering data simultaneously, and I'm excited to see how students respond and develop with practice! Next post: sense-making discussion.

4 Comments

|

AuthorHi! I'm a bio/chem teacher and M.S.Ed. student at the University of Pennsylvania. Archives

April 2018

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly